By Capt. Peeush Kumar

‘Pilot-error’ events in aviation are seldom cheap and catastrophes amongst helicopter operations not very rare. Factoring that operator hands over multi-crores worth of machine to individuals who must keep themselves sharp is up for a talk. Any aviation business house with foresight mitigates failure modes in its human and machine elements. Contemporary machines have fortunately matured to a stage where even single engine helicopters are being certified for operations under IFR (Instrument Flying Rules). On-board avionics are pleasantly reliable. In fact, efficiency of autopilots recently triggered much ado about pilots keeping in touch with ‘hands-on’ flying skills!Implicitly and evidently,a reasonable majority of unfortunate incidents/accidents involved ‘cockpit-human’ error and much less the machines. The human element indeed wedges itself for an opportunity to upgrade.

Regulations help keep safety on top,but quintessentially address a minor subset of real-world challenges. An operator typically juggles between interests of company’s stakeholders against operational, regulatory, administrative&overhead costs. Pilots as ‘front-desk’ are influenced by said elements to add on to their personal & professional obligations.Resultant background stress thus needs effective management especially when handling expensive machines in a complex Indian Helicopter ecosystem. Cockpit is a unique workplace where one/two minds make critical, on-the-spot decisions with little room for error; a widely different setup from a typical office. Here, operators could play an assistive role to help reduce stress levels amongst these cockpit-humans in favour of business interests.

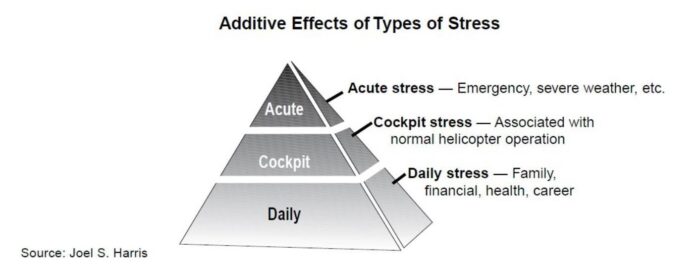

Stress management for Helicopter Pilots has been dealt interestingly by Flight Safety Foundation. An indicative breakdown about origins of stress and its levels is adapted below from one of its journals[1].

Pilots attempt to keep accumulated cockpit & daily stress from affecting flight safety. Both categories have majority elements possible to influence during preparation stages itself. Cockpit stress scenarios could be owed to poor helipad preparation affecting landings, inadequate helipad security jeopardising helicopter safety, unacceptable fuel quality risking flight safety or even unsatisfactory administrative arrangements at helipads. Acute stress elements on the other hand are usually burst of challenging situations. Here, in-flight emergencies, unexpected weather conditions, unacceptable helipad condition like situations demand quick, accurate and decisive reactions for safe recovery. It is obvious that all such situations cannot be encountered/visualised during training. The crew is therefore required to get creative under stress for a safe outcome. Good quality of recurrent training and regular internal performance assessments by operators can assist reducing possibilities of major upsets from such acute stress situations.

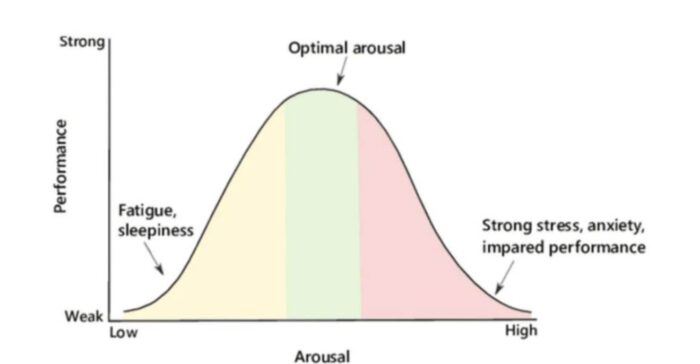

Underlying role of operator in a collaborative approach for mitigating crew stress is the core of talking point. Many elements of Acute, Cockpit and Daily stress could be positively influenced by operator to favour business sustainability.Stress, nevertheless does not have ‘BAD’ written all over. Some magnitude of stress even helps performance as suggested by Yerkes–Dodson law[2]figured below. Maintaining clear of the ‘wrong side’ on this curve requires an honest and collaborative intent in workplace.

Managing ‘Daily stress’ largely rests within an individual’s personal domain. Succeeding paras deal with‘Cockpit and Daily Stress’ elements where an operator can help people handling its expensive machine(s).

Crew-Scheduling. Humans are social beings. Uncertain crew-scheduling triggers non-committal approach of individuals to personal social obligations. Since unsure of their presence on a future date, an anxiety accompanied acceptance of social invitation senses. For an individual, sporadic participation in social events affects his/her primary societal characteristic. Repeat occurrences cumulatively wears out fabric of personal social engagement, and is indeed stressful. Should aforesaid appear benign, consider consistently missing anniversaries, birthdays, religious events at home or even socials/get- together with acquaintances.

A solution maybe found in cooperative, flexible crew scheduling system for onshore operations where regulatory fatigue limits are only arrived occasionally. In this flexible arrangement, crew and operator balance business obligations with social empathy on a two-way street within regulatory framework. Offshore helicopter operations on the other hand pivot heavily on regulated crew fatigue limits that restrains flexibility in crew-scheduling.Possibly, an efficient crew scheduling software managed compassionately could offer respite in these cases.

Fatigue Limits and Sleep-Debt. Regulated fatigue limits when considered as the ultimate upper boundary instead of a business target to achieve consolidates succeeding content. Agreeably, aviation business imperatives lie on the opposite side of aforesaid idea. A balancing act by mitigating resulting hazards could thus be contemplated. Sleep-debt and crew fatigue can possibly be ‘softened’ with good quality accommodation and corresponding administrative arrangements. Consider example of crew post eight-hour duty period waiting at airport for transport to hotel, finding a sub-status hotel on arrival, and a wanting food quality there adding to heightened stress levels. Fit this scenario on a late evening when the crew needs a quick rest after preparation for next day’s flight(s).

Sleep-debt leads to micro-sleep where an individual is asleep for a few seconds and the brain isn’t processing [3]. The brain flips rapidly between being asleep and being awake. Each sleep period lasts for only a few seconds.Naturally, this is not a condition to let develop for personnel dealing with expensive equipment and priceless lives.Finally, reproduced below are extracts from para 8-1-1 (f), Chapter 8, FAA Aeronautical Information Manual [4]concerning stress and fatigue. It seems fitting to conclude author’s argument to deal empathetically with humans of helicopter cockpit for business sustainability.

“Stress from the pressures of everyday living can impair pilot performance, often in very subtle ways. Difficulties, particularly at work, can occupy thought processes enough to markedly decrease alertness. Distraction can so interfere with judgment that unwarranted risks are taken, such as flying into deteriorating weather conditions to keep on schedule. Stress and fatigue (see above) can be an extremely hazardous combination.”

References:-

[1] Vol 21 No 1, January-February 1995, Flight Safety Foundation, Helicopter Safety: For Helicopter Pilots, Managing Stress is part of Flying Safely.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yerkes%E2%80%93Dodson_law

[3] https://www.webmd.com/sleep-disorders/what-to-know-microsleep

[4] https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/aim_html/chap8_section_1.html

About The Author:

Capt Peeush Kumar is a certified Type Rating Examiner (TRE) on H145 Helicopter managing Flight Operations for anon-scheduled operator. He is a certified Experimental Test Pilot (Rotary Wing), and an active author for various aviation periodicals. Hispaper about Fight Testing orientation in Indian ecosystem was published in a journal during International Flight Test Seminar of Aircraft and Systems Testing Establishment, Indian Air Force. Capt Peeush Kumar has been in pursuit of safer PBN (Performance Based Navigation) procedures for helicopters through active approach and awareness initiatives.He is reachable at: Peeush_Saini@yahoo.co.in

Courtesy (Top Banner Pix) By SC National Guard – wikimedia